NOTE: Because of our snow day, I had to make some schedule changes, which means I pushed everything back one day. So the paper is NOT due next Thursday, actually the following Monday, February 22nd (instead of the 17th). Also, I'm going to cut the scheduled reading for Tuesday, and go to the next one, which is the selection of Anglo-Saxon riddles from the book. There are MANY riddles scattered throughout the book, so I chose a few from each section below:

Selected Riddles for Tuesday:

* Riddle 4, "Busy from Time to Time" (p.75)

* Riddle 5, "I am a Monad Gashed by Iron" (p.77)

* Riddle 7, "All that Adorns Me Keeps Me" (p.77)

* Riddle 8, "I Can Chortle Away in Any Voice" (p.79)

* Riddle 13, "I Saw Ten of the Them..." (p.87)

* Riddle 16, "All My Life's a Struggle..." (p.151)

* Riddle 23, "Wob is My Name..." (p.161)

* Riddle 24 & 25 (pp.163)

* Riddle 50, "I Dance Like Flames" (p.265)

* Riddle 33, "A Sea Monster..." (p.269)

* Riddle 43, "A Noble Guest..." & "A King Who Keeps to Himself" (pp.317 & 319--two versions of the same riddle!)

* Riddles 44-45 (p.321)

* Riddle 47, "A Moth Ate Words" (p.323)

* Riddle 51, "I Saw Four Beings" (p.407)

* Riddle 65, "Alive I Was" (p.449)

* Riddle 68-69, "I Saw That Creature..." (p.451)

* Riddle 75-76, "I Saw Her..." (p.455)

* Riddle 79-80, "I Am a Prince's..." (p.457)

As you read these riddles, think about some of the following ideas...

* Try to solve as many of the riddles as you can. The answers are hidden in the back of the book if you get desperate, however! You can also Google "Exeter Book Riddles" to find alternative translations, which could also help.

* The word "riddle" comes from the Old English "raedan," which means "to advise, counsel, guide, explain." How do some of these riddles seem to illustrate the riddler's relationship the world? Or, how does it change the way we see/experience the world after riddling it?

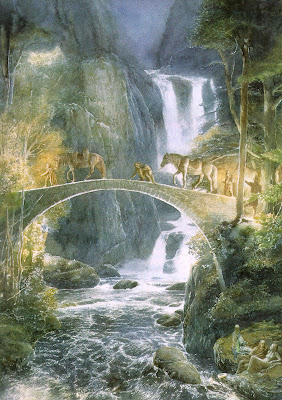

* Where do we hear echoes of Gollum and Bilbo's riddles in this collection? Which ones might Tolkien have most borrowed from for The Hobbit?

* Based on the solutions to these Riddles (I'm sure you can guess some of them), what kinds of items/things were important to the Anglo-Saxon world? Why do you think this is? What themes/items seem to crop up the most?

* One of the delights of the riddles is how they can throw you off the scent, and think you're reading something entirely different. How does one of the Riddles do this--make it seem like it's talking about something completely different, though once you know the answer, it's obvious that the meaning never changed.

* Which Riddles do you feel are most like a poem? Why might you not even need to solve it to appreciate its message? In fact, why might many of the poems make sure that there ISN'T one right answer, but several? How do they do this?

.jpg)

.jpeg)